Audi F1 2026 fire-up: the milestone that matters

Meta Description: Audi F1 2026 fire-up signals the power unit is alive in the R26 chassis, turning years of work into track-ready integration progress.

Subhead: Audi’s first full-car fire-up isn’t a headline for diehards only. It’s the moment a modern hybrid program becomes a working system with real deadlines.

Formula One teams love to say they’re “on schedule.” The sport almost forces them to. Deadlines are fixed, freight leaves when it leaves, and the first race doesn’t care how ambitious your slide deck looked last spring.

You may also like: https://www.testmiles.com/cadillac-barcelona-f1-shakedown-testing-livery-explained/

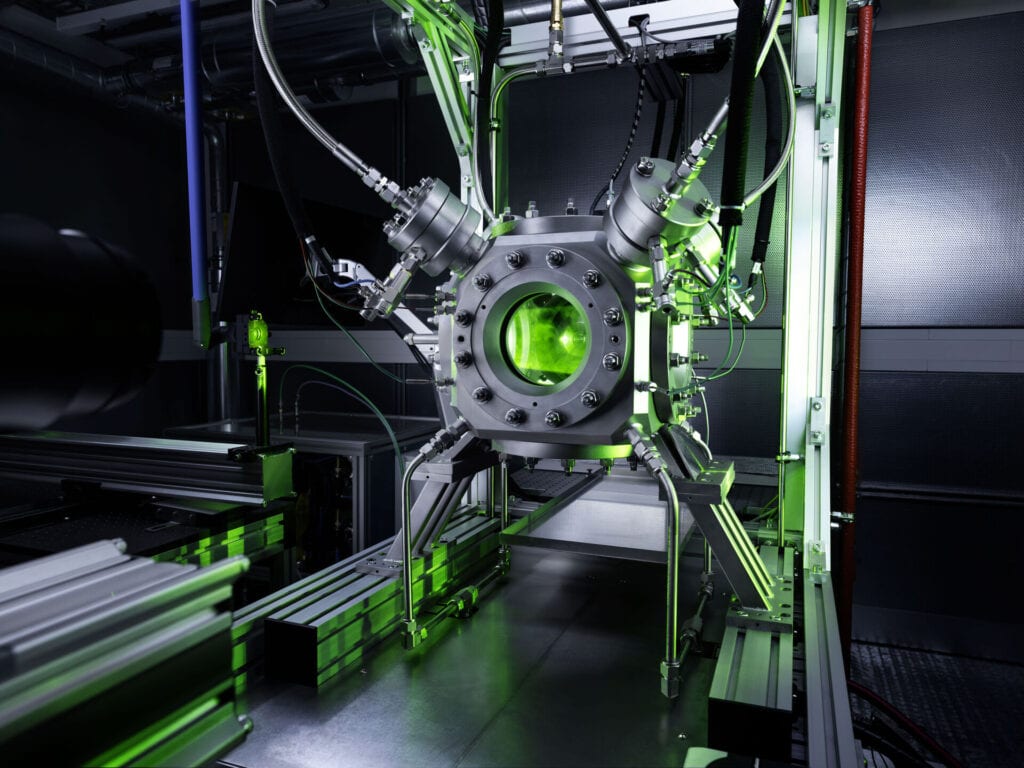

That’s what makes Audi’s latest milestone worth your time. On December 19, 2025, Audi successfully fired up its 2026 car for the first time with the Audi Power Unit installed in the chassis at Hinwil. Audi publicly framed it as the first time the power unit had been run while mounted in the car—an integration gate that turns a long-running engineering project into something you can finally test as a complete system. Audi’s own announcement is here: Audi Revolut F1 Team ignites 2026 campaign with successful first fire-up.

In normal language: it lived. And in a sport where “it lives” can be surprisingly hard, that matters.

If you like the human side of big engineering programs, Audi’s story also has a clear theme. The fire-up is the product of years of parallel work across Neuburg (the power unit operation in Germany), Hinwil (the chassis base in Switzerland), and Bicester (a newer UK technical center meant to help the team tap into Motorsport Valley talent and suppliers). That multi-site structure can be a competitive advantage—if, and only if, the interfaces are clear and the collaboration is real.

You may also like: https://www.testmiles.com/hot-wheels-f1-movie-die-cast-car-brad-pitt/

And because this is the automotive world, not just the racing world, it’s hard not to connect this moment to what’s happening on the road. Your modern car is already a rolling integration challenge: high-voltage systems, complex thermal loops, software-defined power delivery, and driver-assistance hardware that depends on clean data and consistent calibration. Formula One is simply doing it at maximum intensity.

For a broader sense of how motorsport pressure can shape road-car thinking, you might enjoy Cadillac Barcelona F1 Shakedown Livery Explained, which breaks down how much of an “F1 moment” is really about engineering habits and information control.

Why does this matter right now?

Because Audi is entering at the exact moment Formula One’s powertrain philosophy shifts again. The 2026 regulations push the sport toward a different hybrid balance and a different energy-management game. If you want a plain, official explanation of what’s changing in the power units, Formula One’s own overview is the cleanest place to start: F1’s power units: how they work and what’s changing for 2026.

This matters for Audi because new regulations don’t just reshuffle lap times. They reshuffle risk. They change what “good” looks like in a power unit—how you deploy energy, how you harvest it, how you keep temperatures stable, and how you ensure reliability when everything is new and everyone is chasing the same performance targets under a cost cap.

A fire-up is not a lap time, but it is one of the first moments you can say something concrete. It confirms that the power unit, chassis, electronics, control software, cooling systems, and safety interlocks can function together in real hardware. That’s a bigger deal than it sounds. Plenty of components can look healthy in isolation. The first true argument happens when they share a single car.

Audi has been building toward this for a while. In mid-2024, Audi publicly discussed its progress running a complete power unit on test benches and covering simulated race distances—important groundwork because it reduces the chance that your first chassis integration turns into an emergency. You can see Audi’s earlier milestone framing in its power unit development update: Development of the Audi Power Unit for Formula 1: significant milestones achieved.

But there’s no substitute for the real thing. Once the car can be started as an integrated system, the team can begin the most valuable phase of any new program: correlation. Does what you see in simulations match what the sensors see on the car? Does the cooling behave as modeled? Do the control strategies respond consistently? Do vibrations and packaging constraints reveal problems you didn’t have on the bench? That learning loop is where performance begins.

It also lands right before a fixed calendar. Audi’s announcement points to a Berlin launch on January 20, 2026, followed by the first collective test window in Barcelona at the end of January. Formula One and the FIA have already confirmed the early testing schedule, including the private Barcelona session. That official testing calendar is here: Formula 1 confirms 2026 pre-season testing dates.

If you’re the kind of reader who likes deadlines because they force clarity, this is the moment Audi’s project starts being measurable. The car can now run. The next question becomes: how quickly can it learn?

How does it compare to rivals or alternatives?

Audi’s project is best understood in two comparisons: competitive rivals inside Formula One, and the broader manufacturer “why are we here?” question.

On the competitive side, Audi is aiming to arrive as a true works effort: an engine program and a chassis program designed under one umbrella, with the ability to make packaging and integration decisions that customer teams often can’t. That can be an advantage in a new rules era where small compromises become big performance losses. The cost is that you inherit every problem. If your cooling concept is wrong, it’s your problem. If your software architecture needs rework, it’s your problem. The upside of a supplier relationship—someone else owns the engine headaches—doesn’t exist for a full factory program.

It’s also worth noting that Audi’s identity is now tied to a title partnership that reflects how modern F1 teams fund and scale. Revolut’s deal to become title partner for the Audi F1 effort was widely reported, including by Reuters: Revolut to become title partner of Audi F1 team. Sponsorship isn’t just stickers; it’s often operational integration, tech collaboration, and the budget certainty needed to hire and retain top-tier engineers.

As an “alternative” narrative, compare Audi’s moment to the other big 2026 newcomer story that American audiences will hear a lot about: Cadillac entering Formula One. Cadillac’s entry is a different structure and a different brand story, but it shares the same hard truth—projects mature when deadlines arrive. If you want a consumer-friendly view of how these global racing bets connect back to road cars, Cadillac Vistiq: The Electric Three-Row That Actually Works is a good reminder that “performance” for many buyers now includes software confidence and real-world usability, not just acceleration numbers.

You may also like: https://www.testmiles.com/2026-cadillac-vistiq-seven-seat-electric-suv-super-cruise-range/

The fairest takeaway right now is this: Audi’s fire-up suggests the program is clearing the right gates on the right timeline. It does not tell you the car will be fast. It tells you the team can begin the work that eventually produces speed: track running, correlation, reliability cycles, and relentless iteration.

Who is this for and who should skip it?

This is for you if you like the engineering side of the car world—how systems come together, how software shapes performance, and how modern hybrid strategies are as much about control logic as they are about mechanical design.

It’s also for anyone who enjoys watching a big organization try to execute under pressure. Audi isn’t just “joining F1.” It’s building a three-site technical operation, hiring experienced leadership, and trying to establish a competitive culture while the entire sport resets its technical rulebook. That is hard. It’s also interesting in a way that goes beyond motorsport fandom.

You may also like: https://www.testmiles.com/from-formula-one-to-family-driveways-gm-racing-strategy/

And yes, it’s relevant even if your day-to-day life is family transport rather than lap charts. The same themes that show up in F1 power units—thermal management, energy recovery, software-defined power delivery—show up in the cars you buy or lease, just tuned for longevity and comfort instead of outright pace. If you’ve been following the broader mobility conversation, Robotaxis in 2026: Are We Ready for Driverless Cities? makes a similar point from a different angle: the future of transport is increasingly “systems + software,” and that changes how we judge competence.

You should skip this if you only want predictions. A fire-up is a competence milestone, not a competitive result. It’s also not the place to look for driver drama or podium forecasts. Those stories will arrive once there’s track time, race pace data, and a few hard weekends where nothing goes to plan.

What is the long-term significance?

In the long run, Audi’s fire-up is a signpost for where performance brands are heading.

First, it reinforces that modern performance is no longer purely mechanical. It is mechanical plus electrical plus software. The winning formula isn’t simply “a great engine.” It’s a complete energy system—one that can harvest, store, deploy, and survive under stress. If you want to read the exact, technical shape of the new-era rules, the FIA’s regulations are the source document: 2026 Formula 1 Power Unit Technical Regulations (PDF).

Second, it highlights how motorsport now functions as an organizational forcing function. F1 doesn’t just test a part. It tests a company’s ability to integrate disciplines quickly: electrical engineers, combustion specialists, software teams, thermal experts, manufacturing, quality control, and operations. That capability doesn’t stay in one building forever. It tends to influence how a manufacturer approaches product development, even if the road-car results are indirect and slow-burn.

Third, the timeline is a reminder that electrification is not a single decision; it’s an integration project. Many consumers think of electrification as a choice between “gas” and “electric.” But the reality—especially for hybrid systems—is a layered architecture of energy flows, heat flows, and control strategies. That’s why a first fire-up can be meaningful beyond racing. It’s an early sign that the layers can operate as a coherent whole.

If you want a surprisingly useful analogy from the luxury world, consider what Rolls-Royce is doing when it invests heavily to scale complex, custom work: it’s building capability, not just selling products. That mindset—capability as the real asset—is covered well in Rolls-Royce Bespoke boom: $380M Goodwood expansion.

Audi’s F1 project is similar in spirit. The first fire-up isn’t a trophy. It’s a capability milestone. It means the machine exists, it has breathed, and now the team has to prove it can learn fast enough—on track, under pressure—before the sport’s new era stops being a promise and becomes a scoreboard.

And if you’re thinking, “This all sounds expensive,” you’re not wrong. But that’s true in the consumer market as well. Complex systems cost money, whether they’re built for a grid in Melbourne or a driveway in America. If you want a grounded look at how policy, technology, and market structure show up in prices, That New Car Is $6,400 More Expensive. Here’s Why. is a useful companion read.

The calm conclusion is this: Audi’s first integrated fire-up doesn’t tell you how competitive they’ll be. It tells you they’ve crossed one of the first honest gates. From here forward, the sport will do what it always does—measure everything, expose weaknesses quickly, and reward the teams that can improve without losing their nerve.